Biography - V

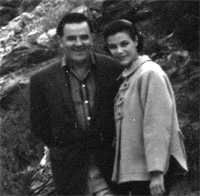

Louis and Kathy L'Amour, near the location

where Heller with a Gun was being filmed

as Heller in Pink Tights. (c. 1959-60)

n 1956

Louis L'Amour married Katherine Elizabeth Adams, an aspiring

actress. The daughter of a resort developer and silent movie

star, Kathy had grown up in the deserts and mountains of Southern

California where her father had once owned vast tracts of land.

Together they traveled all over the west searching out locations

and doing research for Louis' books. In 1961 their son Beau was

born and in 1964 they had a daughter, Angelique.

n 1956

Louis L'Amour married Katherine Elizabeth Adams, an aspiring

actress. The daughter of a resort developer and silent movie

star, Kathy had grown up in the deserts and mountains of Southern

California where her father had once owned vast tracts of land.

Together they traveled all over the west searching out locations

and doing research for Louis' books. In 1961 their son Beau was

born and in 1964 they had a daughter, Angelique.

The 1960s were a productive time for Louis. He developed his famous Sackett family series, traveled extensively to promote books and movies, and, for the first time in his life, bought a house. He was often invited to speak at public forums and held book signings for large crowds all across the country. And he finally settled down to work with a single publisher, Bantam Books.

After six years (1953 -1959) of going back and forth between Fawcett/Gold Medal, Ace and Bantam, Louis was looking to find a publisher who would bring out more than two of his books per year. His editor at Gold Medal lobbied to let him write more but management refused even though he was placing books with competing publishers. L’Amour had sold 14 novels, 9 motion pictures, and several million paperback copies before Bantam Editor in Chief Saul David was finally able to convince his company to offer Louis an exclusive contract that would expand to three books a year. It was only after 1960, however, that Louis’s sales at Bantam began to surpass his sales at Gold Medal.

The 1970s were years of financial success, despite this, however, Louis later signed a thirty book contract with Bantam to keep himself motivated and on a deadline. Louis expanded the Sackett family series to include the family's beginnings on the American continent and also began the process of weaving in tales of the Chantry and Talon clans too. The vision of a large matrix of fiction interwoven with the history of the United States and Canada began to appear in his work. Plans, many that did not come to fruition for another ten years, for writing historical fiction (like The Walking Drum, a story written in the 1960s but not sold until the mid '80s.) and even science or fantasy fiction (The Haunted Mesa) were carefully made. By 1973 his new found wealth allowed Louis to move into a better neighborhood in West Los Angeles. Louis felt independent and secure for the first time in his adult life. He was sixty-five years old.

Even before the height of his success in the 1980s, jealousy caused some controversy among other writers of westerns. A rumor was circulated that somehow Louis was a creation of his publisher, Bantam Books, and that they told him what to write and then gave him preferential treatment over other writers when it came to money and advertising. In truth, Louis wrote in a manner that was very much like stream of consciousness and it was nearly impossible for him to plan what was going to happen in one of his books let alone take direction from someone else. On several occasions, when financial pressures seemed overwhelming, Louis took jobs writing for various movie studios. In most cases he opted to return the money, no matter the financial hardship he was in, rather than struggle to write at the direction of someone else. He simply couldn’t do it.

Even in the early 1970s, Bantam Books was still

lagging in the area of public relations, it took a publicity trip

to England and the exemplary efforts of L’Amour’s British

publisher Corgi, to focus their attention on what could be done.

For the most part the publicity effort that defined Louis’s

career until the mid ‘70s was the work he did on his own, learned

through hard experience promoting both boxers and his own book of

poetry in the 1930s. Publishers then, as now, spent next to

nothing unless they absolutely had to.

Even in the early 1970s, Bantam Books was still

lagging in the area of public relations, it took a publicity trip

to England and the exemplary efforts of L’Amour’s British

publisher Corgi, to focus their attention on what could be done.

For the most part the publicity effort that defined Louis’s

career until the mid ‘70s was the work he did on his own, learned

through hard experience promoting both boxers and his own book of

poetry in the 1930s. Publishers then, as now, spent next to

nothing unless they absolutely had to.

The hard feelings seem to have culminated with the story that Bantam required independent distributors to buy titles in lots of 10,000 copies if they wanted access to other Bantam titles at wholesale prices, and that they kept all of L’Amour’s books in print at all times . . . thus forcing other authors off the racks in the Western sections of bookstores.

“There were occasionally additional price incentives offered to distributors who sold certain amounts of the entire Bantam catalogue,” George Fisher, who worked at Ludington News in Detroit, the number two independent distributor in the country, remembers. “But selling Louis was often the way that a distributor could meet their quotas, because he was so popular. Louis wasn’t a problem for us, he was a solution.”

The problem seemed to be one of jealousy and misinterpretation, writers with fewer titles and less popular books could get squeezed where shelf space was limited. But no publisher could afford to keep books in print that weren’t selling, the book stores would simply return them for a refund. Whatever the effect, Louis L’Amour was not the beneficiary of any sort of special, and exclusive, distribution policy.

Discover luxury replica hublot watches at ReplicaFactory! Expertly crafted with Swiss movements, sapphire glass, and 1:1 detailing. Perfect for gifting or self-indulgence. Water-resistant, scratch-proof, and indistinguishable from originals.